Secondary sources

What distinguishes a very good written task 2 from a mediocre one? Besides answering the expectations of the prescribed question, good WT2s cite both primary and secondary sources. In other words they comment on a text (primary source) and refer to other texts (secondary sources) that have also commented on the original text. Secondary sources, if used properly, can validate the ideas that are expressed in an essay. Secondary sources can also be used to guide, plan and structure the WT2 essay.

What distinguishes a very good written task 2 from a mediocre one? Besides answering the expectations of the prescribed question, good WT2s cite both primary and secondary sources. In other words they comment on a text (primary source) and refer to other texts (secondary sources) that have also commented on the original text. Secondary sources, if used properly, can validate the ideas that are expressed in an essay. Secondary sources can also be used to guide, plan and structure the WT2 essay.

In this lesson we will look at how secondary sources can be used to build a critical response to ‘The Kite Runner’ by Khaled Hosseini. With a few simple steps you can see how a WT2 is built around a few secondary sources.

Relevant questions

First of all it is important to establish which of the six prescribed questions are relevant to the text that you have read. This kind of decision can be made quite quickly. Place all six questions on a table and discuss with others which ones are most relevant to the text studied. Give reasons for your choices.

-

How could the text be read and interpreted differently by two different readers?

A Pashtun / Afghan may read this differently than an American or western reader.

A Pashtun / Afghan may read this differently than an American or western reader.

-

If the text had been written in a different time or place or language or for a different audience, how and why might it differ?

This question is fraught with difficulties and opens the door to circular reasoning.

This question is fraught with difficulties and opens the door to circular reasoning.

-

How and why is a social group represented in a particular way?

The Hazara are represented as humble and subservient. The Pashtun are forceful (Rahim Khan) and rather secular (Baba). And the Taliban are down right evil (later chapters).

The Hazara are represented as humble and subservient. The Pashtun are forceful (Rahim Khan) and rather secular (Baba). And the Taliban are down right evil (later chapters).

-

Which social groups are marginalized, excluded or silenced within the text?

The Hazara’s are not given a strong voice. They are silenced within the text by Rahim Khan and even Amir.

The Hazara’s are not given a strong voice. They are silenced within the text by Rahim Khan and even Amir.

-

How does the text conform to, or deviate from, the conventions of a particular genre, and for what purpose?

This question is not very relevant, as the novel has many of the typical structural features of modern novels.

This question is not very relevant, as the novel has many of the typical structural features of modern novels.

-

How has the text borrowed from other texts, and with what effects?

One could argue that it is a modern Huckleberry Finn, but this essay would require extensive and possibly irrelevant research.

One could argue that it is a modern Huckleberry Finn, but this essay would require extensive and possibly irrelevant research.

Research

The next step is to find good secondary sources. As we live in the digital age, it is tempting to do a quick and easy search online. While a lot may be written about your primary source online, it may not all be of high quality. Pulling ideas off Spark Notes is not advised for your WT2 research. While such sites may steer you in the right direction and point to the pertinent questions, they do not offer much original, critical insight into literary works. So what are sources of higher quality?

- Enotes.com – This is a big step up from Spark Notes, because, besides offering plot summaries and character descriptions, it includes well-written critical analyses by professional teachers and authors. For this reason there is a subscription fee.

- Ebsco Host – If your school does not already have a subscription, you may want to sign up for a free trial. You will be amazed by the amount of high quality articles from scholarly journals that are easy to find and age appropriate.

- Books – Remember these? Many great authors still only publish in book (or ebook) form. If your library does not have the resource you’re looking for, your librarian may be able to help you get your hands on a physical copy.

If you do not have the funds to access quality information on- or offline, then it helps to know how to search properly online. It also helps to work with a text that is highly read and reviewed. As you can see from these list of poor and good search terms, it is useful to think about the types of texts that will serve as reference material.

Poor search terms / sources

|

Good search terms / sources

|

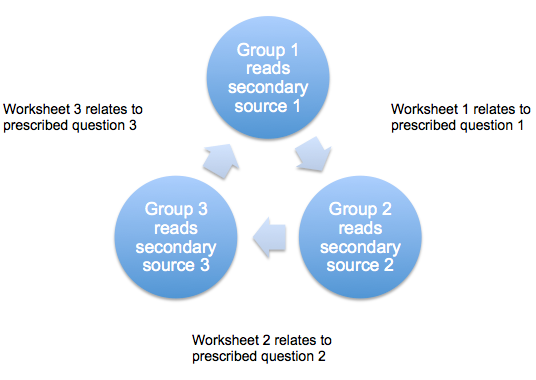

Relevance of questions to secondary sources

Once to you have three or four good secondary sources, try to find their relevance to the prescribed questions that you have chosen. It is useful to do this as a jigsaw reading activity, where each expert group reads one secondary source and explains its relevance to each of the prescribed questions as they are rotated around the groups. For this reason it helps to have the same number of secondary sources as prescribed questions. Circulate the worksheets through each expert group for five to ten minutes per group, and you are left with a nice overview of secondary sources that are relevant to each of the prescribed questions.

![]() Secondary sources and the written task 2

Secondary sources and the written task 2

Example of Worksheet 1

Prescribed question 1: "How could a text be read and interpreted differently by two different readers?”

| Secondary source 1 | Secondary source 2 | Secondary source 3 | |

| How might the author of your secondary source respond to the prescribed question above? | |||

| What lines could you quote from your secondary source, which are relevant to the prescribed question above? | |||

| Where in the primary source can you find examples of what the secondary source is commenting on? |

Secondary sources

Secondargy source 1

'The Kite Runner'

Mabel D Khawaja

Master Plots (Salem Press)

Nov. 2010

The Kite Runner is Khaled Hosseini's first novel. Born in Kabul, Hosseini draws heavily on his own experiences to create the setting for the novel; the characters, however, are fictional. Hosseini's plot shows historical realism, as the novel includes dates--for chronological accuracy, including the time of the changing regimes of Afghanistan. Amir's happy childhood days fall under the peaceful and affluent era of King Zahir Shah's reign, a time when Amir and his friend, Hassan, could themselves feel like kings of Kabul, carving their names into a tree. In 1973, Dawood Khan becomes the president of Afghanistan. This era is reflected in the novel when the local bully, Assef, harasses Amir with his brass knuckles and hopes that Hazaras will be eliminated.

The Kite Runner is Khaled Hosseini's first novel. Born in Kabul, Hosseini draws heavily on his own experiences to create the setting for the novel; the characters, however, are fictional. Hosseini's plot shows historical realism, as the novel includes dates--for chronological accuracy, including the time of the changing regimes of Afghanistan. Amir's happy childhood days fall under the peaceful and affluent era of King Zahir Shah's reign, a time when Amir and his friend, Hassan, could themselves feel like kings of Kabul, carving their names into a tree. In 1973, Dawood Khan becomes the president of Afghanistan. This era is reflected in the novel when the local bully, Assef, harasses Amir with his brass knuckles and hopes that Hazaras will be eliminated.

The Russian invasion in 1981 turns Kabul into a war zone, forcing many residents, including Baba and Amir, to escape to Pakistan. Even after the Russians had left the country, the unrest had continued. In 1996, the Talibs had come to power. In the novel, Rahim Khan tells Amir that Talibs had banned kite fighting in 1996 and that in 1998, Hazaras had been massacred.

The novel's complex plot consists of several conflicts that evoke sympathy for characters who are unjustly victimized. The story begins with the internal conflicts of Amir--a wealthy child--who enjoys Hassan's friendship but is also jealous of him and ends up cheating him. An external conflict occurs between the protagonist, Amir, and the antagonist, Assef. Amir goes to Afghanistan to rescue his nephew Sohrab, as "a way to be good again," but encounters Assef, a vindictive and cruel enemy from the past, and now a ruling Talib.

A final conflict shows the gap between the legal system and the human rights of orphans as victims of war, a gap that leads to Sohrab's attempted suicide. Intrinsic to the conflicts in the novel is the unjust victimization of the innocent--a theme evoking the import of human rights across international boundaries.

Hosseini succeeds in striking the right balance between tragic emotion and optimism. For example, the narrator drops clues that Sohrab will talk again "almost a year" after his suicide attempt. Similarly, Sohrab's faint smile in the novel's last scene is a clue that he will be happy with his new guardians. Hosseini's imagery also is powerful and layered with meaning. For example, Sohrab hitting Assef with slingshot fire is a befitting image that shows the triumph of the weak and lowly over the high and mighty--a modern David and Goliath tale.

Another successful aspect of the novel is characterization. When Amir's character transforms, he is willing to risk his life for Sohrab. In contrast, Assef claims a religious conversion but shows no change of character. Some critics find fault with Hosseini's one-dimensional characterization of Assef as a stereotyped Talib who is inhumane and tyrannical. However, the novel is written from a first-person narrator's viewpoint. Amir is the narrator for twenty-four chapters, and Rahim Khan narrates the events of the past in chapter 16. Both narrators can report only their respective experiences, and both paint a tragic picture of Taliban atrocities.

Unique to Hosseini is his artistic ability to blend the literary tradition of the Western novel with the Persian literature of the Sufis. The novel includes consistent references to the Persian legend of Rostam and Sohrab, which comes from Persian poet Firdusi's Shahnamah (c. 1010), the poetic epic of Afghanistan, Iran, and other Persian-speaking countries. These references serve to exemplify the novel's theme, a classic one, of the quest for the father. Other parallels with the Persian epic are The Kite Runner's ironic revelations about the past, the novel's war-zone setting, and the novel's tragic irony associated with the ignorance of many of its characters. Tragic irony is a vehicle for revelation, and it also serves as a rhetorical strategy to validate the narrator's claim: "I've learned . . . [how] the past claws its way out." Likewise, tragic irony becomes a rhetorical strategy for comparing and contrasting characters' behaviors as they manipulate knowledge and claim ignorance in their relationships. For example, Amir's childish ploys to get rid of Hassan and his father, Ali, culminate in a tragic scene, in which "Hassan knew . . . everything. . . . He knew I had betrayed him and yet he was rescuing me once again." Hassan would not expose to Baba that Amir was actually a liar and a cheater. This marks a critical moment in Amir's life because he realizes that he loves Hassan, "more than he had loved anyone else"; still, Amir cannot confess the truth and will never again see Hassan.

The Kite Runneris a powerful story about two boys whose friendship is threatened by deception and betrayal yet withstands the pressures of cultural barriers and legal boundaries. Their childhood memories of happy days outlast their tragic separation, and the steadfast loyalty of Hassan defines the theme of this novel as one of true friendship.

Secondary source 2

''The Kite Runner' Critiqued: New Orientalism Goes to the Big Screen'

Matthew T. Miller

Common Dreams

Jan. 2008

While The Kite Runner movie is now captivating audiences throughout the country-much as the book did four years ago-with its enthralling tale of "family, forgiveness, and friendship" and the promise that indeed "there is a way to be good again," very little has been written critiquing this work and its prominent role in the New Orientalist narrative of the Islamic Middle East.

While The Kite Runner movie is now captivating audiences throughout the country-much as the book did four years ago-with its enthralling tale of "family, forgiveness, and friendship" and the promise that indeed "there is a way to be good again," very little has been written critiquing this work and its prominent role in the New Orientalist narrative of the Islamic Middle East.

Iranian literature specialist Dr. Fatemeh Keshavarz (Washington University in St. Louis) has classified this book as one of the recent works that she argues constitute a "New Orientalist" narrative in her book Jasmine and Stars: Reading More than Lolita in Tehran. (Dr. Hamid Dabashi of Columbia University also has written about New Orientalism and expatriates who serve as "native informers" or "comprador intellectuals" in respect to the Middle East).

Keshavarz broadly characterizes the New Orientalist works thusly: Thematically, they stay focused on the public phobia [of Islam and the Islamic world]: blind faith and cruelty, political underdevelopment, and women's social and sexual repression. They provide a mix of fear and intrigue-the basis for a blank check for the use of force in the region and Western self-affirmation. Perhaps not all the authors intend to sound the trumpet of war. But the divided, black-and-white world they hold before the reader leaves little room for anything other than surrender to the inevitability of conflict between the West and the Middle East.

While The Kite Runner is perhaps less obvious in its demonization of the Muslim world and glorification of the Western world-what Keshavarz terms the "Islamization of Evil" and the "Westernization of Goodness"-than books like Reading Lolita in Tehran, these themes nevertheless clearly permeate the entire novel. While seemingly just a captivating story of Amir and his redemption through the heroic rescue of his childhood friend Hassan's son, Sohrab, the entire plot is imbued with noxious stereotypes about Islam and the Islamic world. This story, read in isolation, may indeed just be inspiring and heart-warming, but the significance of its underlying message in the current geopolitical context cannot be ignored.

At the most superficial level, the characters and their accompanying traits serve to advance a very specific agenda: everything from the conspicuous secularity of the great hero, Amir's father, Baba, to the pedophilic Taliban (i.e. Muslim) executioner and nemesis of Amir, Assef, clearly perpetuates the basic underlying theme: the West (and Western values) = 'good,' while Islam = 'bad,' or even, 'evil.' The inherent goodness of Baba and evil of Assef is repeatedly reified for the reader in some of the most dramatic and graphic scenes of the entire book. Baba valiantly lays his life on the line to protect the woman who is about to be raped, while Assef brutally rapes children and performs gruesome public executions in the local soccer stadium. Yet, perhaps the most telling attribute of these two characters is the particular national ideologies that they express affinity for: Baba loves America, while Assef is an admirer of Hitler.

The most pernicious element of this novel, however, is also the same aspect that American readers consistently have identified as the most heart-warming and inspiring: the story of the redemption of Amir thorough his harrowing and heroic rescue of Sohrab. In short, Amir, the successful western expatriate writer must leave his safe, idyllic existence in the U.S.; return to an Afghanistan that has been ravaged by the Russians (our Cold War enemy) and the Taliban (the representation of our new Islamic enemy); and rescue the innocent orphaned son of his childhood friend from the incarnation of evil itself, Assef. Amir's descent into this Other World, a veritable 'heart of darkness,' appears to be the only hope for its victims' salvation.

This adventurous and engrossing story neatly functions as an allegorized version of the colonial/neo-colonial/imperial imperative of "intervening" in "dark" countries in order to save the sub-human Others who would be otherwise simply lost in their own ignorance and brutality. These magnanimous interventions, of course, have nothing to do with economic or geopolitical concerns; they are purely self-sacrificial expressions of the superiority of the imperial peoples' humanity and ideology. When considered in this frame, the profound guilt that Amir suffers from his inaction during the violation of his innocent friend Hassan seems to represent the collective guilt of all "good" western or western-oriented people who watched idly while the Islamic bullies-epitomized by Assef-violated Afghanistan and the innocent western-oriented people like Baba and Amir. Of course, the implication then is that we also must redeem ourselves by returning and "rescuing" the people there from the Assefs of Afghanistan-this is our "way to be good again," in the words Khaled Hosseini's character Rahim Khan. This new recapitulation of the old "white man's [now, western] burden" narrative, when combined with the "Westernization of Goodness" and "Islamization of Evil" clearly present throughout the novel, provides a superb ideological framework upon which to justify our present occupation and future military interventions in Afghanistan.

It certainly does not take much imagination to expand this story and its message to the entire Islamic Middle East-especially when we combine this work's portrayal of Afghanistan with the other New Orientalist works on the Islamic Middle East, such as Azar Nafisi's popular Reading Lolita in Tehran, Asne Seierstad's The Bookseller of Kabul, Geraldine Brooks' Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women, and even scholarly works like Bernard Lewis' What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response. If what these works say about Islam and Islamic countries is the whole truth, then surely the continued and expanding U.S. military presence in that region is a good thing, right?

For anyone who has been to, or studies the Middle East, it is obvious that these accounts are gross distortions of the full reality on the ground there. It is not wrong to identify and write about the flaws of a particular country, religion, or ideology, but it is wrong and dishonest when an author's writings systematically dehumanizes and reduces an entire culture and religion to the actions of its extremists. Especially, when these are the same people and countries that our leaders tell us need to be attacked and occupied by our military.

Secondary source 3

Dialogue with Khaled Hosseini

Farhad Azar

Lemar-Aftaab Afghan Magazine

June 2004

Khaled Hosseini enjoys telling stories. In his debut novel The Kite Runner, he narrates a deeply reflective tale. Hosseini's work provides an indigenous look into an Afghan experience, which some critiques have considered as a more realistic account of Afghans and Afghanistan than any work produced by even the best journalists. We spoke with Hosseini about his novel, perspectives and forthcoming work.

Khaled Hosseini enjoys telling stories. In his debut novel The Kite Runner, he narrates a deeply reflective tale. Hosseini's work provides an indigenous look into an Afghan experience, which some critiques have considered as a more realistic account of Afghans and Afghanistan than any work produced by even the best journalists. We spoke with Hosseini about his novel, perspectives and forthcoming work.

Farhad Azad: What do you think your novel has provided in representing Afghanistan to the Western readers?

Khaled Hosseini: I think --and hope-- that the novel has provided Western readers with a fresh perspective. Too often, stories about Afghanistan center around the various wars, the opium trade, the war on terrorism. Preciously little is said about the Afghan people themselves, their culture, their traditions, how they lived in their country and how they manage abroad as exiles. I hope The Kite Runner gives the Western reader some insight into and a sense of the identity of Afghan people that they may not get from mainstream news media. Fiction is a wonderful medium to convey such things. And I hope that the book helps humanize the Afghan people and put a personal face to what has happened there. I get many letters and e-mails from readers who say how much more compassion they feel for Afghanistan and Afghans after reading this book --some even offering to help or donate money. We forget sometimes that fiction can be a powerful medium that way.

FA: What is the general and specific reactions of the Western and Afghan readers to your work?

KH: My Western readers have had a very positive reaction to The Kite Runner. Because the themes of friendship, betrayal, guilt, redemption, the uneasy love between fathers and sons are universal themes and not specifically Afghan, the book has been able to reach across cultural, racial, religious, and gender gaps to resonate with readers of varying backgrounds.

The reaction from my Afghan readers has also been overwhelmingly positive. I get regular letters and e-mails from fellow Afghans who have enjoyed the book, seen their own lives, experiences, and memories played out on the pages. So I have been thrilled with the response from my own community.

Some, however, have called the book divisive and objected to some of the issues raised in the book, namely; racism, discrimination, ethnic inequality etc. Those are sensitive issues in the Afghan world, but they are also important ones, and I certainly do not believe they should be taboo. The role of fiction is to talk about difficult subjects, precisely about things that make us cringe or make us uncomfortable, or things that generate debate and perhaps some understanding. I think talking plainly about issues that have hounded Afghanistan for a long time is a healthy and a necessity, particularly at this crucial time.

FA: Why do you think these taboo topics such as "racism, discrimination, ethnic inequality" in the Afghan society should be exposed and discussed in the Afghan Diaspora? Why do you think such topics are avoided and not discussed by the general Afghan Diaspora? And how do you think the Afghan Diaspora can better discuss these topics?

KH: Fiction is often like a mirror. It reflects what is beautiful and noble in us, but also at time what is less than flattering, things that make us wince and not want to look anymore. Issues like discrimination and persecution, racism, etc. are such things. The rifts between our different people in Afghanistan have existed for a long time and continue to exist today, no matter the politically correct official party line. Because these issues of ethnic differences and problems between the different groups continue to hound our society and threaten to undermine our progress toward a better tomorrow, I think --possibly naively-- these issues are best dealt with face on. I don't see how we can move forward from our past; how we can overcome our differences, if we refuse to even acknowledge the past and the differences.

FA: The Afghanistan of the 1960s - 1970s has been described as the "Golden Years" by the majority of the older generation of Afghans in the Diaspora. You vividly describe this period through the eyes of the novel's main character Amir, which is also a period of history that has not really been disclosed by Western writers. Yet your approach is also critical of the bitter, unjust realities of that era, contradictory to the one-sided impressions of the older Afghan generation. What is your response?

KH: My intention was to write about Afghanistan in a balanced fashion. I also remember the 1960's and particularly the early to mid 1970's as a Golden Era of sorts. I, like many Afghans, look back on those years with fondness and remembrance. I have tried to portray that era lovingly through the eyes of Amir. However, that society was not perfect. There were inequities and inequalities that got lost in the glow of remembrance. We should also remember that there was racism, discrimination, rampant nepotism, and social barriers that were all but impossible to cross from, at times, entire classes of people. One example that I highlight in my book is the mistreatment of the Hazara people, who were all but banned from the higher appointments of society and forced to play a second-class citizen role. A critical eye toward that era is, I believe, as important as a loving eye, because there are lessons to be learned from our own past.

FA: The first two sections of the novel cover 1970s Afghanistan and 1980s Northern California, which you have personally experienced. How did you write so clearly the accounts of life under 1990s Taliban Afghanistan?

KH:I primarily relied on the accounts of Afghans who had lived in Afghanistan in that era. Over the years, at Afghan gatherings, parties, melahs [picnics], I had spoken to various Afghans who had lived in Taliban-ruled Kabul. When I sat down to write the final third of The Kite Runner, I found I had unintentionally accumulated over the years a wealth of anecdotes, telling details, stories, and accounts about Kabul in those days. So I did not have to do much research at all. Of course, I also relied on media reports through Afghan online magazines, TV, radio, etc. But most of it was from Afghan eyewitness accounts.

FA: You had mentioned that the character Hassan was the original protagonist of the novel. Why did you change it to Amir?

Amir is so much more conflicted than Hassan. He is such a troubled character, so flawed. He is often a contradiction. He wants to be a good person and is horrified at his own moral shortcomings even as he can't stop himself. In other words, he is a better protagonist for a novel -maybe I should say more dynamic-- than Hassan, who is so firmly rooted in goodness and integrity. There was a lot more room for character development with Amir than Hassan.

FA: What specific aspects of the Afghan Diaspora are represented in Amir's character?

KH: Nostalgia and longing for the homeland. The preservation of culture and language: Amir marries an Afghan woman and stays an active member of the Afghan community in the East Bay; the hard-working immigrant value system; and some sense of survivor's guilt, which I think many of us, particularly in sunny California, have felt at one time or another.

FA: Some critics have stated that the ending of your novel is "too clean" and have attributed this to perhaps you trying to "make sense" of the many years of turbulence in Afghanistan by providing closure with the ending. What is your reaction?

KH: I think it is largely a matter of taste. What strikes one person as "too neat" makes a resounding impact with another reader and registers as a welcomed sense of closure. I did not want to end my book with chaos and hopelessness. The Kite Runner ends on a hopeful --if melancholic-- note. Which is how I also feel about the future of Afghanistan --guarded optimism. To some extent, as a writer, you do try to make sense of the turbulence and chaos, and with the words at your disposal you have the option and power to do so. The question is whether you do it with integrity and honesty and whether you stay true to your characters and their dilemmas. I believe I have. Or I tried, at least. As always, the reader is the judge.

FA: Will your next work also take a historic journey to Afghanistan's recent past?

KH: The writing process has always been full of surprises for me. The story takes unexpected twists and turns and that, to me, is one of the joys of writing. Which is to say I rarely can describe with much detail what I am working on. I begin writing and see where the story takes me. That said, the novel I have been working on is also set in Afghanistan and deals with its recent history. It has a female protagonist and deals more with women's issues than The Kite Runner did. Beyond that, I'll be able to tell you more in 12-18 months.

FA: What classical and contemporary Afghan literature where you influenced by?

KH: The writing of The Kite Runner was not influenced by any Afghan literature per se, though I have admired the works of writers such as Mr. Akram Osman. I read quite a bit of fiction in English, and I would say that my style and approach to writing is rooted in a western style of writing prose. That said, Afghanistan is full of great storytellers, and I was raised around people who were very adept at capturing an audience's attention with their storytelling skills. I have been told that there is an old fashioned sense of story telling in The Kite Runner. I would agree. It's what I like to read, and what I like to write.

FA: How important is it to tell a story of a people from an indigenous perspective rather than from an outsider's point of view?

KH: I think your specific background, your upbringing, your intimacy with the culture, customs, language and ways of your homeland gives you an angle that a writer who is not indigenous to your country may lack. It gives you a unique perspective, an angle. That is not to say that an outsider cannot write as well about your culture. I am thinking of Andre Dubus III and the wonderful job he did bringing to life Colonel Behrani in House of Sand and Fog. But usually, being indigenous allows you a little authenticity and if you write with honesty and integrity, then it may show on the pages.

FA: You always say that you want to tell stories. What drives you do this?

KH: I don't quite know where the drive to tell a story comes from, for me or anyone else. Nor do I really know where the stories themselves come from. What I can say that for me, as I suspect for many other writers, a story grips me and demands to be told. The drive to tell a story becomes a compulsion. So there is little choice left. You either tell the story or go around absent-minded and in a half-daze. Stephen King once said that if you have a story to tell and the skill to tell it, and you don't, then you are a monkey. The point is stories, good stories at least, demand to be written.

More secondary sources on The Kite Runner

An Afghan hounded by his past

An Afghan hounded by his past

Amelia Hill

The Observer

7 September 2003

The Journey Home

Khaled Hosseini

The Guardian

18 December 2004

The Servant

Edward Howard

New York Times Book Review

3 August 2003

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

Sue Bond

Asian Review of Books

19 July 2003

Kite Runner: A Pyschological Operation?

Dr. Rahmat Rabi Zirakyar

Sabawoon Online

5 December 2009

In-text citations

Once you have extracted a few lines from the secondary (and primary) sources that you plan to use for your written task 2, it is time to embed and integrate them into your essay. For help on how to integrate sources best into an essay, see the skills page on integrating quotations for Paper 1. In contrast to Paper 1, written task 2 is a take-home assignment, meaning that you can do research. It is recommended that you follow the Modern Language Association's (MLA) style guide on how to cite sources, which is explained in detail on the University of Purdue's OWL website. Here you will notice that MLA does not encourage the use of footnotes (which, unfortunately are commonly used by IB DP students). Instead one should use such structures for citing (ditigal) sources: (Notice especially the positioning of quotation marks, parenthesis and periods (full-stops).)

Digital source

The novel's protagonist, Amir, "wants to be a good person and is horrified at his own moral shortcomings even as he can't stop himself" (Azar, 'Dialogue with Khaled Hosseini').

Digital source with author's name in-text

The Kite Runner has also been very divisive, as it paints a very black and white picture of East and West. As Mattew T. Miller has suggested, The Kite Runner "leaves little room for anything other than surrender to the inevitability of conflict between the West and the Middle East" (''The Kite Runner' Critiqued: New Orientalism Goes to the Big Screen').

Digital source with author's name and source in text

In Mabel D. Khawaja's essay on The Kite Runner in 'Masterplots', she explains how the novel succeeds in intriguing the reader, as its "complex plot consists of several conflicts that evoke sympathy for characters who are unjustly victimized."

Works citied

The written task 2 is one of the few opportunities for students to include a bibliography or 'works cited'. 'Works cited' is the tem preferred by the MLA and it follows a very detailed structure. It is necessary to follow this structure in coordination with the in-text citations to make references clear for the reader. How does one remember the complex structure of 'works cited'? Again, it is recommended to consult the OWL page on this as well. There is also a short cut, which is highly recommended here. It is called 'easybib.com'. Not only does this website place all of the right information in to the correct position, it searches the Internet for supplementary information on the source. The following three examples were created in Easy Bib for the three sources on The Kite Runner.

Works cited

"Dialogue with Khaled Hosseini." Interview by Farhad Azad. Lemar-Aftaab Afghan Magazine June 2004: n. pag. Print.

Khawaja, Mabel D. "The Kite Runner." Masterplots 12 (2010): Salem Press. Nov. 2010. Web. 10 Jan. 2013.

Miller, Matthew T. "'The Kite Runner' Critiqued: New Orientalism Goes to the Big Screen | Common Dreams." Common Dreams. N.p., 5 Jan. 2008. Web. 10 Jan. 2013.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team